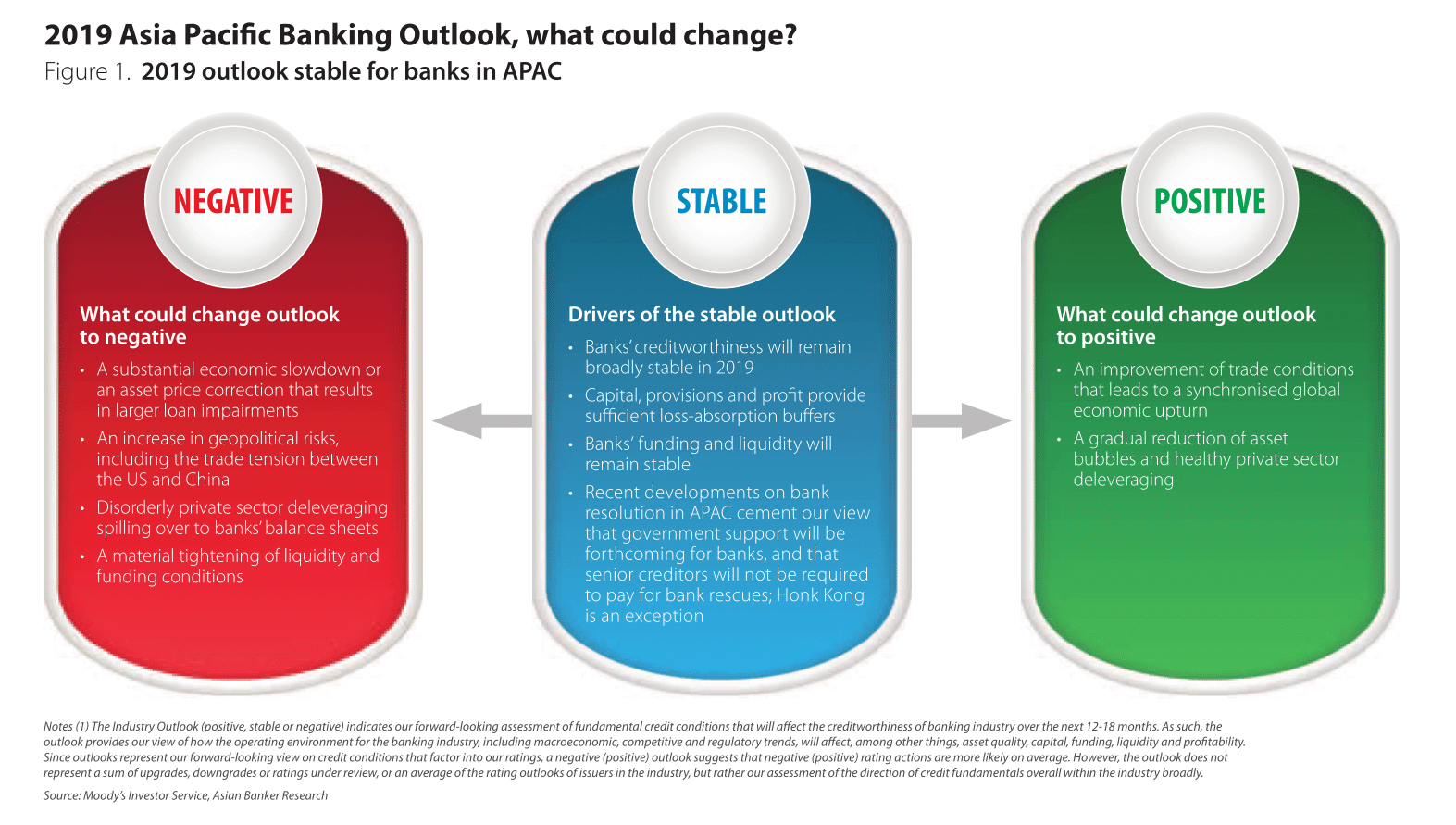

The ‘goldilocks’ growth drivers that delivered a synchronised regional upturn in 2018 have reversed or are missing in new year. First, monetary policy normalisation by the Federal Reserve puts an end to the era of cheaper dollar funding enjoyed by the region to propel growth. A combination of high debt and high asset prices that had evolved over much of Asia Pacific (APAC) during periods of low interest rates, set the stage for a material tightening of liquidity and funding conditions and potential deterioration in credit quality. International credit rating agency Moody’s outlines relative stability for APAC banks in 2019, although it does not rule out the possibility of downside risks at this stage. “What can change our view to more negative assessment are essentially, a much sharper economic slowdown from a fully escalated trade war or restriction on market access to refinancing leading to large nonperforming loans (NPL),” said Eugene Tarzimanov, vice president at Moody’s Investor Service.

Second, APAC is losing steam as second-order impacts (economic slowdown as opposed to direct exposures) of trade and tariff disruptions become more visible, although growth still remains at solid level. Third, once resilient, slowdown in Chinese growth is also having a protracted impact on banks. Crackdown on shadow banking, higher interest rate refinancing for corporates and more stringent rules on NPL recognition point to worsening asset quality “China’s economic slowdown is not only structural but partially cyclical, related largely to negative sentiment from a difficult external environment and slew of anti-corruption measures implemented by the administration,” highlighted Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist for APAC at Natixis.

On a positive note, asset quality remains broadly stable with low levels of NPL in developed markets of Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand and Taiwan, with the exception India where NPL remains elevated. Strong buffer, higher capital adequacy ratios (CAR) and sufficient loss-absorption capacities limit any downside risks in most of key markets.

Incorporating ‘government support’ expectations in its ratings actions, Moody’s believes that government support remains strong for systemically significant institutions in Asia relative to other regions. Hong Kong remains an outlier to the region, with the recently implemented alternate resolution frameworks.

While opportunities from accelerating fintech development to collaborate and grow market share represents a winwin situation for banks and technology companies, it also heightens risks from price competition and aggressive and at times- unproductive investments in technology. The impact of fintech on banking system to date remains unclear from a credit point of view. “Immediate impact on credit ratings of banks is yet to be seen as improvements in financial efficiency at banks would take some years to materialise,” remarked Tarzimanov.

While general outlook for APAC banks remains stable, 2019 could bring forth challenges which would accelerate the build-up of economic imbalances, taking a toll on credit quality of banks. Here are some of the contributing factors that may influence and impact the regional outlook.

US-China trade skirmish will alter supply chains

Potential impact from US-China tariff is unevenly distributed across the region’s economies. Intermediate product exporters with direct exposure to China stand to lose while those able to capture a part of the manufacturing chain to export directly to US stand to gain. Although not a grave concern for now, banks and corporates sitting on complex supply chains may have to adjust to new sourcing patterns, sooner or later.

Corporates and households are overleveraged

Concerns over private corporate and household sector debt are not new to the region. Although many countries have administered programs to smoothen the process of deleveraging, success is not guaranteed. “Rising US dollar interest rates expose banks to the risk of asset quality impairment,” Tarzimanov emphasised.

Strong growth of household debt in Australia, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore and Thailand and corporate sector excesses (largely packaged as loans to real-estate) in China and Hong Kong are of particular concern. Though emerging markets (EMs) of Bangladesh, India, Indonesia and Sri Lanka are relatively less leveraged as a percentage of their GDPs, they house companies failing to fulfil creditor obligations.

But all is not lost! Ratio of private sector debt to GDP is coming down as flow of credit to private sector is restrained. Exposure of both shadow and traditional bank lending to real-estate sector in China is on a decline, but so is financing for more productive small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and private owned enterprises (POEs), Garcia-Herrero noted.

A volatile year for EMs

Battered by rising US interest rates and strengthening US dollar, instances of foreign capital fleeing fundamentally weak Asian EMs is a recurring theme. Net-oil importers with weaker currencies (especially India, Indonesia and Thailand) running persistent current account deficits represent conducive cases of spilling over these risks onto banking system balance sheets.

Where is the new credit?

Lack of monetary policy traction to anchor credit growth in productive pockets of the Chinese economy, despite more cuts in the Reserve Requirements Ratio (RRR) indicates a broken transmission mechanism. In addition to steep decline in shadow banking, massive injections of credit have failed to translate into bank lending. It is this “bottleneck in China’s monetary policy” that is impeding flow of credit to the more productive SME and private sectors, Garcia-Herrero observed.

Another issue is that the rapid drop in China’s money market rate, SHIBOR (Shanghai Interbank Offered Rate), which failed to mirror the real cost of funding for companies in the private sector. To address these issues, The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has resorted to implement more administered rates of credit, but by stepping backwards on financial liberalisation. Garcia-Herrero views consequences of this backpedalling to be unfavourable to Chinese banks’ profitability and asset quality.

Capital provisioning remains high

Risk-adjusted capital ratios in most jurisdictions continue to strengthen, underpinned by moderate growth in risk-weighted assets (RWAs), implementation of BASEL III standards among other stringent regulatory requirements and reasonably sound internal capital generation prospects. High capital buffers in relatively developed markets of APAC provides ability to withstand shocks, should financial distress deepen.

Moody’s identified negative outliers with lower capital provisioning in markets of India, Sri Lanka and Vietnam. Asset quality in India compares less favourably to rest of the region, prompting authorities to infuse public sector banks via its recapitalisation plan.

Largely contained but NPLs could rise moderately

NPL ratios remain largely stable and below 1.8%, particularly across developed markets in APAC including Australia, China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand and Taiwan with the exception of India, Indonesia, Mongolia and Vietnam. Problem loan ratios in 2019 for developing Asia are expected to improve as absorption process of NPLs comes to its tail end.

Although most financial institutions (FIs) in APAC can withstand some deterioration in their asset quality ratios in 2019, some remain vulnerable to volatility in equity and commodity prices and lower economic growth.

Impact from a no-deal Brexit

There remains a significant risk that the UK parliament will not approve the deal between the UK and EU. While UK banks remain vulnerable to a no-deal Brexit with limited access to cheaper wholesale funding, what could be some of the impacts in Asia?

Garcia-Herrero sees immediate impact of a no-deal Brexit on the offshore financial centres in APAC, particularly on the dominant role of Hong Kong in lending to the Mainland. For Tarzimanov, the impact will remain limited as both offshore hubs of Singapore and Hong Kong are well established to serve ASEAN and mainland China. Further, limited or no lending exposure of Asian banks to companies in UK diminishes any probability of contagion.

In conclusion, 2019 outlook for the majority of APAC banks remains stable. Banks will continue to experience moderate to slightly above average growth in their loan assets. Despite some margin pressure, profitability is sound as most banks have put in place, measures to reduce operational costs. Asset quality, as measured by levels of NPLs has stabilised, though is still high in some markets. With sufficient capital accumulated over the post financial crisis period, banks are in good shape to weather the downside risks.