New developments in financial technology, the improved availability of public personal information, better internet bandwidth, minimal regulations, and underdeveloped or concentrated markets have given rise to alternative lending platforms. One of these is crowdlending, which connects lenders with borrowers without the intermediation by banks. Unlike banks, crowdlending platforms generally do not earn a margin on the loan, instead they charge fees.

The main distinguishing factor to (equity) crowdfunding is that the borrower has the obligation to pay back the money with a fixed payment schedule and at a fixed interest rate.

Since there is an obligation to pay back from the beginning, loans are only given to companies or projects that are already generating cash.

Crowdlending is expected to grow to over $800 billion in terms of loans origination by 2020. Specifically, Asia Pacific, mainly driven by China, is forecast to overtake other regions, with a projected 72% share of aggregated loan issuance (Figure 1).

(1).jpg)

Crowdlending in Asia Pacific countries

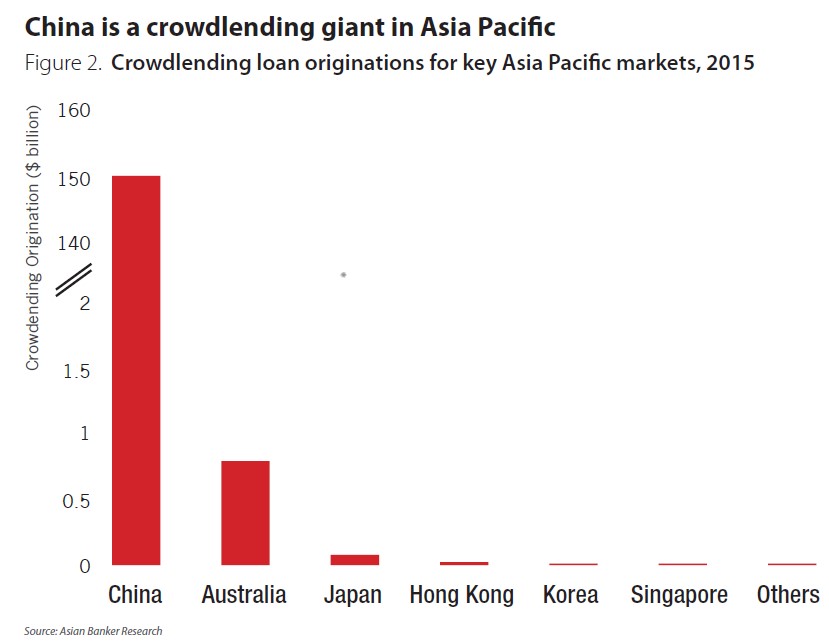

In 2015, around 2,600 P2P lenders representing 96% of the roughly 2,700 crowdlenders in the region were based in China, from where $150 billion worth of loans originated (Figure 2).

China

Although China’s total loan origination is valued at around $113 billion by local Chinese crowdlending trackers, there is lack of transparency in the data presented by the platforms. Accurate data is hard to track due to the swelling number of players, lack of transparency, as well as malpractices at the lower end of the market.

China is a crowdlending giant in Asia Pacific. In China, the banking sector is marked by tight credit conditions and a focus on corporate loans. The concept of crowdlending was first introduced in the Chinese market by CreditEase in 2006.

“The inception of P2P lending (in China) was unorthodox and home-grown. We had no knowledge what other countries were doing. This innovative business model harnesses the power of the masses and is perceived as contrary to the principles of traditional banking. Yet the business model is sustainable and has potential, despite having had a rough initial phase where customers were trying to understand the products better, and required education,” remarked CreditEase CEO and founder Ning Tang.

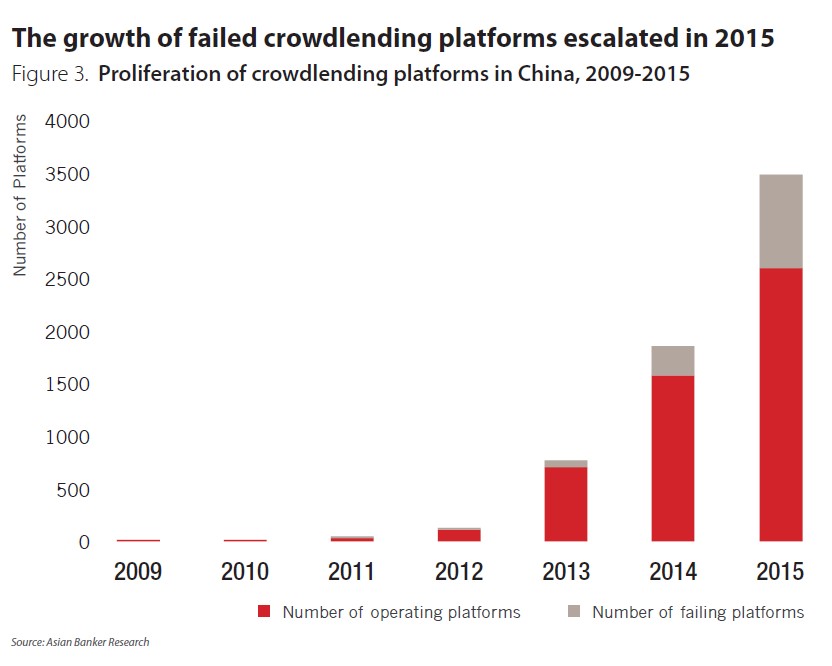

Soon after CreditEase was launched, other crowdlending platforms followed such as Paipaidai (2007) and Lufax (2012). In just nine years, the total number of platforms reached 2,595 (Figure 3).

In 2015, 896 platforms reported operational problems ranging from frozen accounts to CEOs taking flight without notice. Since mid-2015, net growth of crowdlending platforms began to shrink for the first time, with as many new crowdlenders coming into the market as were exiting. Meanwhile, the number of vanishing crowdlending bosses went up to 266. The famous Ponzi scheme of Ezubao, established in 2014, involved bilking close to a million investors who were promised 15% returns on capital that was plowed into real estate projects of founder Ding Ning.

Tang clarifies that the majority of the failing crowdlending platforms were not operating in, and had no relation to the actual crowdlending business—a “plagiarism of P2P lending by fictitious organisations,” according to him.

Australia

Several foreign and local crowdlenders have entered the Australian retail credit market, taking advantage of spaces where the large Australian banks have voluntarily withdrawn in the last decade: consumer lending and small business. Crowdlending in Australia was initiated in 2012 by the country’s first fully licensed operator, SocietyOne, which was followed by DirectMoney and RateSetter, both established in 2014.

Between 1997 and 2014, the spread between the interest rates paid to depositors and unsecured personal lending rates widened by over 85%. Technology provided the opportunity for a new P2P lending business model that could operate at lower margins and tap into underserved retail segments for personal loans.

The major banks in Australia, which offer 14%–17% interest rates on personal loans, currently have a market share of approximately 80%. Of this, 75% of retail lending is concentrated on mortgage lending. At present, there are seven major crowdlending players in Australia offering rates that are around 8%–10% lower for similar loans: DirectMoney, Marketlend, MoneyPlace, OnDeck, Ratesetter, SocietyOne, and ThinCats Australia.

RateSetter in Australia is a spin-off from the UK-based P2P platform of the same name, which was launched in 2010. CEO Daniel Foggo shares that he studied different business models that solved what he thought was really the problem in Australia: the chasm between savers and borrowers. RateSetter, through its unsecured and secured personal loans, aims to narrow this gap.

Singapore

Crowdlending has been available through three platforms in Singapore since 2014. To date, these have originated $12 million in loans, predominantly to SMEs. The first platform to be established, MoolahSense, was founded by Lawrence Yong.

“I felt very intrigued but had to confirm my instincts,” he admitted, “since for most of my career, I was focused on the top 10% where most of the revenue is generated. But if you think about it, many people are still not getting adequately served, most especially the everyday investors and the small borrowers. This spreads across consumer lending and SME lending.”

Crowdlending business models

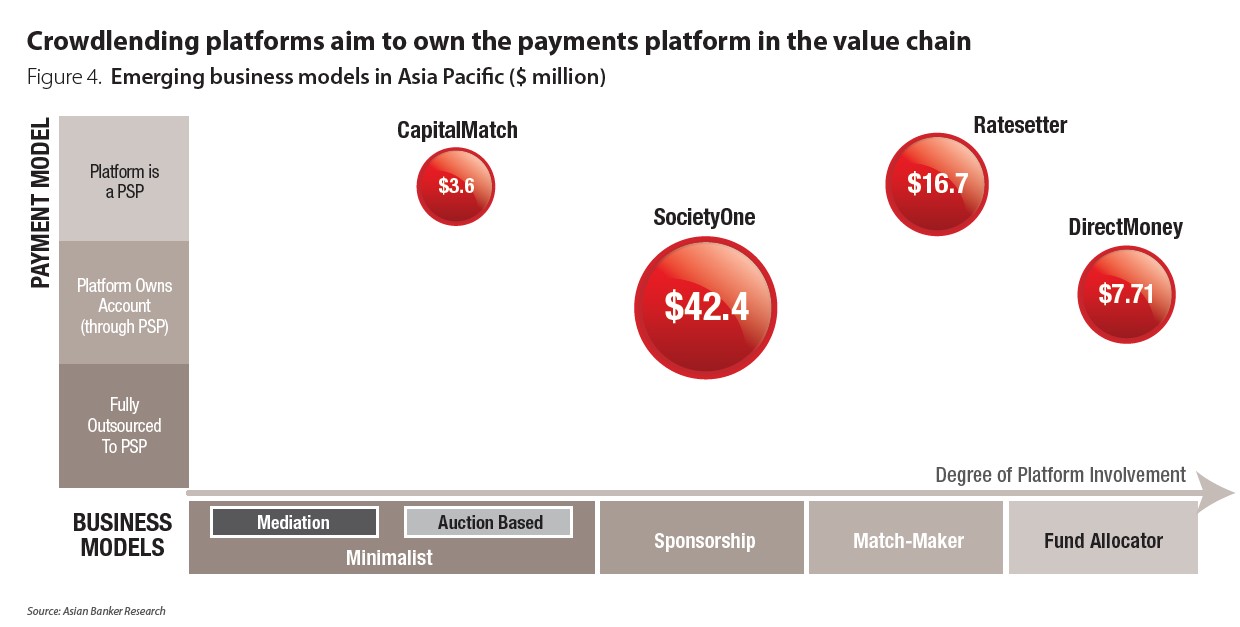

While crowdfunding business models generally involve a platform through which fund seekers advertise their projects to potential lenders, the key market differentiator is the scope of services offered by the platform, such as project evaluation and assignment, ratings of projects, credit assessment, pricing and fee structure, and payments processing.

Below are the emerging crowdlending business models in Asia Pacific:

- Minimalist. The platform provides only a simple framework for the contractual terms, sends contracts to the parties, and coordinates (re)payments. Basically, the platforms extends mediation between the lender(s) and borrowers without an underlying project; or is auction-based, where lenders bid among themselves in an auction and lender(s) selection is based on lowest rates.

- Sponsorship. Financial institutions may make an equity stake and/or provide the loans of the platform. The platform may receive applications from financial institutions that it has reviewed but rejected.

- Marketplace. Investors choose what market to invest in, typically determined by loan term and credit grade. This will be the basis of the platform in matching investor(s) with borrower(s).

- Fund allocator. The platform pools funds from investors then applies it to different borrowers.

Figure 4 differentiates the crowdlending players in the Asia Pacific based on (i) the degree of involvement of the platforms; (ii) their business models; (iii) and their payment handling arrangements (fully outsourced to a payment service provider [PSP], platforms own an account in a PSP, or platform acts as a PSP).

Regulatory environment

The surge in crowdlending activities caught most regulators off guard, and existing frameworks created more uncertainties than stability. Only lately after major excesses and failures are regulators beginning to draft tough new guidelines.

With China tapping into consumption as the new driver of its economy, the government was wary of constricting alternative finance.

In July 2015, local governments introduced a broad internet finance “guidance” policy framework with the principal requirement of establishing a third-party customer fund deposit system in the form of a qualified banking institution that stands behind the crowdlender. The guidance also calls for the integration of information about the crowdlending platform and the credit data accumulated into the People’s Bank of China’s Credit Registry Centre (CRC).

In addition, a set of rules outlined by the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) includes requirements for operators to register with local financial authorities to improve transparency; limit their services to lending and eliminate other offers such as wealth management products; and operate strictly as information intermediaries, not as “credit intermediaries” or pooling platforms.

Meanwhile, Australian crowdlending companies have been running into trouble with Australian regulators. To develop regulatory guidance for the industry and standards for consumer products, DirectMoney and RateSetter have been working in partnership with regulatory bodies, particularly the Australian Securities and Investment Commission. In Australia, any online intermediary platform that facilitates funding for purposes such as crowdlending is classified as an issuer of a financial product and is therefore required to acquire an Australian financial services license.

In Singapore, where crowdlending is still in its infancy, there are no clear rules for the sector. At this stage, operators are interpreting the Securities and Futures Act (SFA) autonomously according to their fundraising methods. Ordinarily, any issuer seeking to issue securities publicly must register a prospectus with the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS). There exists, however, certain exclusions for crowdlending in the form of promissory notes. However, MAS is in the process of drafting specific guidelines for crowdlending and/or funding.

Crowdlending: complementary or competition to banks?

Crowdlending is not yet a fully recognised competitor for most banks due to the higher-risk segments targeted. Moreover, banks are adjusting their own business models rapidly to the new emerging threat.

Due to the inroads crowdlending has created in the retail lending space, banks are adapting technologies similar to crowdlending and are shifting their focus to consumer and SME loans. In early 2015, ICBC launched the first internet finance brand by a bank in China through its e-ICBC initiative. The online platform integrates the bank’s e-commerce business with financial services and includes “Easy Loan”, an online and offline revolving loan

product catering to SMEs with over 4.3 million customers. As of October 2015, Easy Loan had a loan balance exceeding $30 billion and had disbursed $281 billion to over 80,000 SMEs. Meanwhile, ICBC’s online product “Personal Self-service PledgeLoan” has had a total loan issuance of $9 billion. Other banks that have also entered the crowdlending industry are Bank of China and China Merchant’s Bank.

While some banks are fighting the emergence of nonbanks, WestPac and Auswide Bank in Australia are beginning to embrace the presence of crowdlending platforms by entering into equity partnerships with disruptors SocietyOne and Moneyplace, respectively. Through collaboration, banks aim to diversify their financial services, while crowdlending operators receive funding to grow their business.

Crowdlending players have likewise broadened their market reach by partnering with brokers such as RateSetter with Carsales.au and Direct Money with Loan Market and Finsure.

The future of crowdlending in the Asia Pacific

We expect that in the midterm, crowdlending as an alternative lending platform to commercial banking will grow only in very defined niche markets that are unattractive to banks due to their critical mass or risk profiling. In Australia, majority of crowdlending projects are channelled mainly to the small business sector, a segment that has been considerably neglected by large banks since the global financial crisis. Industry observers

estimate that about 10% of SMEs— a market that could be worth $10 billion in lending—face challenges in obtaining funding from traditional sources. However, the crowdlending market in Australia appears to be already overcrowded compared to the United Kingdom and the United States. Moreover, given the small base of loan volume through those platforms, achieving a sustainable and profitable business based on fee income only might be hard to achieve soon.

Even the best commercial banks in Australia would not survive were it not be for their solid interest income. In 2015, Westpac issued A$286 billion ($202.5 billion) in net loans in FY2015, of which 17% A$50 billion ($35.4 billion) was extended to businesses. Fee income from retail payments accounted for 23% of total retail banking income. In comparison, ThinCats Australia, which pursues an auction-based business model, has arranged

loans of $2 million only since it launched in 2014, while hoping to make $1 million each month in 2016. A key challenge is that the crowdlenders do not own the assets nor the payment platform; instead, they own distribution capabilities, which may not be sufficient to survive. Sooner or later, the industry will be forced into a hybrid model of marketplace and traditional balance sheet lender.

Headwinds from regulation and compliance facing crowdlenders are building up. Escalation in operational fraud and failing platforms in China since the second half of 2015 is not only damaging trust, a key asset in financial services, but is triggering tough new licensing restrictions as those to be introduced by the CBRC in 2016. The cost per lending project will inevitably rise for an industry whose income base is razor-thin, making them vulnerable for takeovers or demise all together.

Banks are responding by launching their own innovative online lending solutions or beginning to co-opt them for their own purposes by taking strategic equity stakes in viable crowdlenders. For the remaining online lending platforms such as those in China, they will undergo increased differentiation but it is likely that only P2P platforms run by the large Chinese financial institutions will most likely survive.

.jpg)