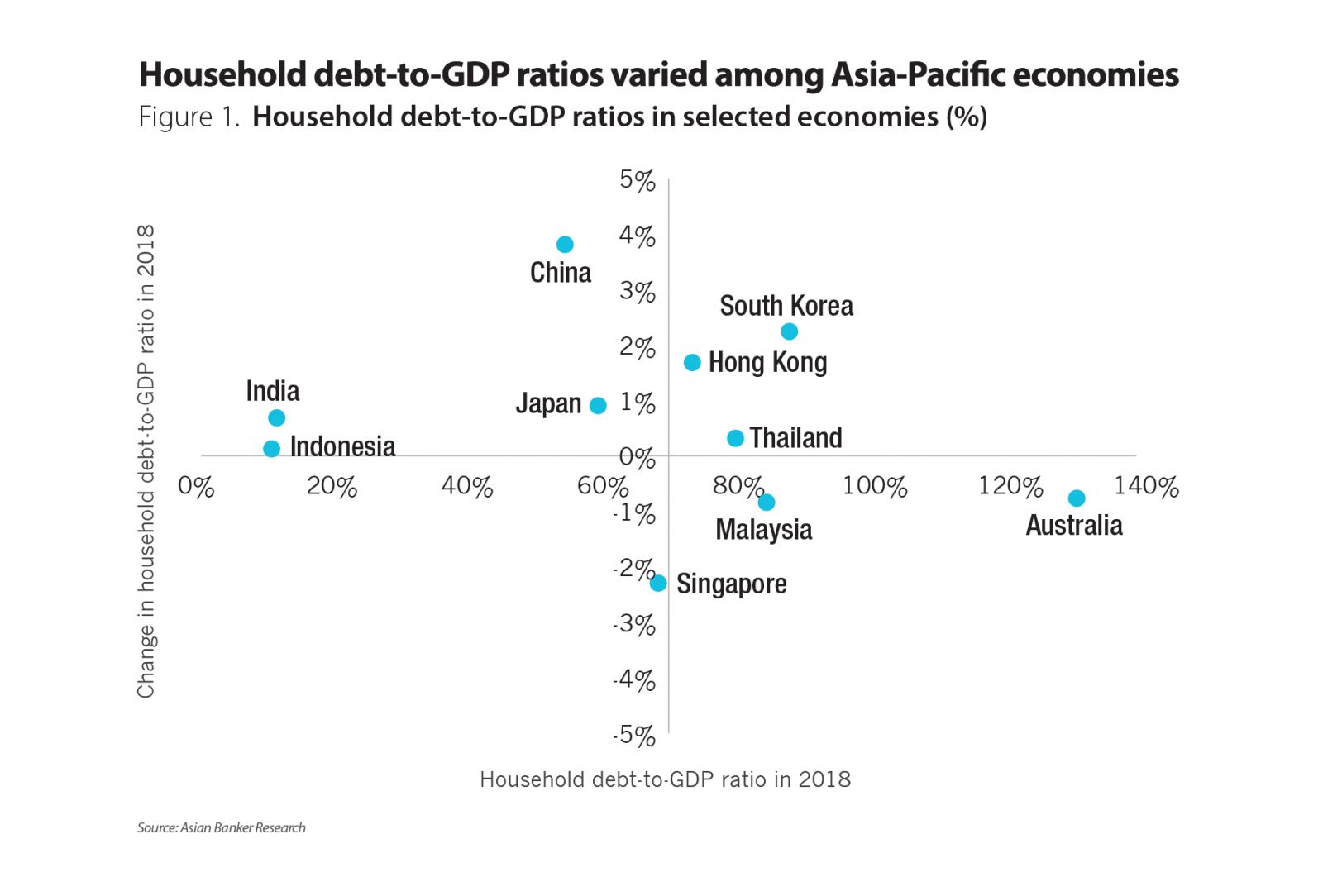

High or rising household debt level remains a constant source of worry in Asia Pacific, which poses risks to economic growth and financial stability. Concerns intensify in many countries as disposable income growth is slower and the economic condition is unfavourable.

Advanced economies tend to have higher ratios of household debt to gross domestic production (GDP). Among the economies we study, Australia has the highest household debt-to-GDP ratio (Figure 1), followed by South Korea, Malaysia, and Thailand. China has witnessed the fastest household debt growth. Household debt problem has resulted in reduced savings or spending in these countries, which is placing the economy under pressure. Household debt also has cast uncertainty on the health of these countries’ financial systems.

Concerns remain in Australia despite slower household debt growth

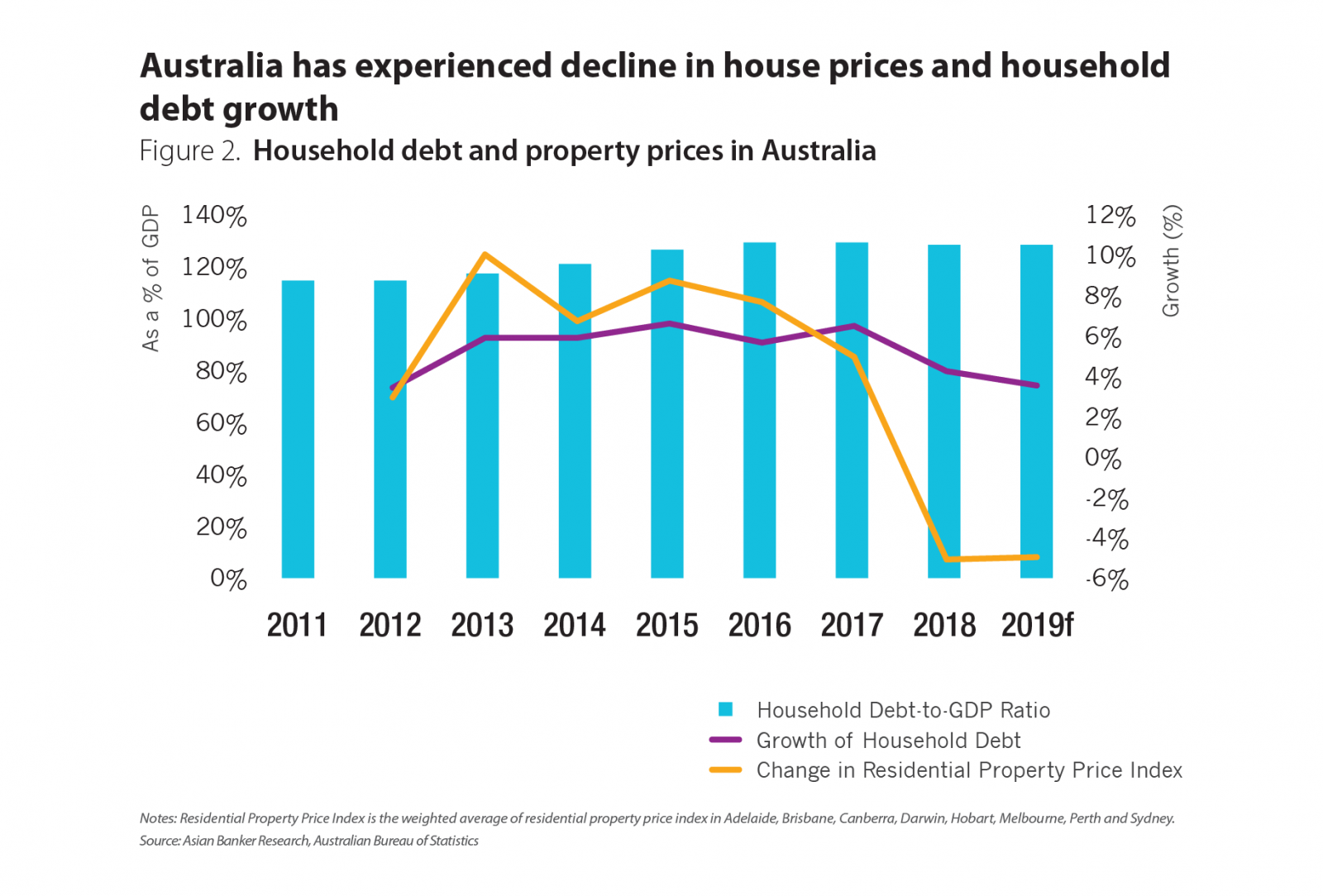

In Australia, household debt as a share of GDP has reached a record high in 2017 (Figure 2), which can be largely attributed to overvalued housing market. Banks have been ordered to impose tougher standards for granting mortgages, which has curbed investment loans and driven home values down. In addition, the Australian property sector was also affected by the restrictions on foreign property buyers in Australia and capital control in China. In 2018, house prices fell substantially in many of Australia’s largest capital city markets. Meanwhile, the growth of household debt decelerated and household debt-to-GDP ratio edged down.

Nevertheless, the house price correction has raised concerns over the housing market slowdown and its impact on household consumption and the economy. The cooling of the housing market has led to reduced household wealth. Figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) show that household net worth dropped by 2.5% in the last quarter of 2018. This is the largest decrease since 2011, following a 0.3% decline in the third quarter of 2018. Meanwhile, the ratio of household debt to disposable income hit a new record of 189.6% in the last quarter of 2018, as the household disposable income grew by just 0.4% in 2018.

The ratio of household savings to disposable income in Australia has dropped significantly in the past few years, as households had to use their savings to support consumption. The growth of Australian household consumption has outpaced the disposable income growth. Households have already spent less due to stagnation in real wage growth, and it is expected that they will cut back their spending further. The current low level of household savings has put Australian households in a vulnerable position, especially at a time when house prices are falling.

The debt deleveraging has started to weigh on already subdued consumer spending via a fading wealth effect. Australia’s GDP growth slowed down considerably in the second half of 2018, with GDP rising only 0.3% in the third quarter of 2018 and 0.2% in the last quarter of 2018, primarily as a result of weak household spending. In early December 2018, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has warned that if Australia’s biggest banks overly restrict their lending during the housing downturn, it will negatively affect the economy. RBA called on the banks not to go too far in curbing the supply of credit to the economy. On 1 January 2019, Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) removed its restrictions on Interest-Only residential mortgage lending for lenders who have proven the strength of their lending standards.

Pace of household debt growth in China has caused concern

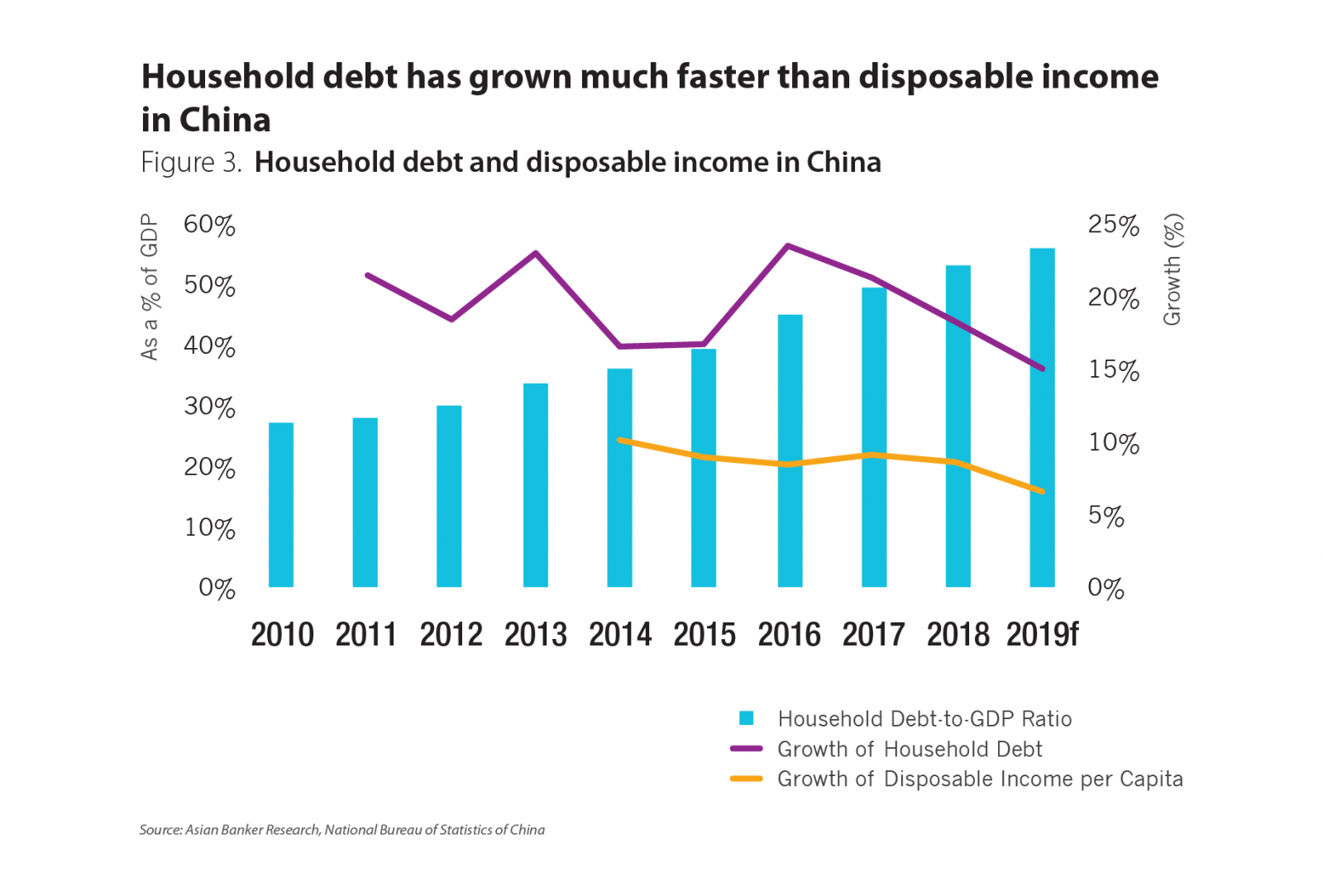

During the period from 2010 to 2018, household debt in China has expanded at a compound annual growth rate of 24%, and household debt as a percentage of GDP was up from 21% to 53% (Figure 3). In China, household debt outpaced corporate debt in early 2018, and new household debt accounts for around half of new loans. The pace of household debt growth has decelerated gradually in the past two years, as financial institutions have tightened lending standards amid the deleveraging efforts. However, household debt as a share of GDP has continued to go up.

The rapid household debt growth has added to the already existing economic growth concerns. China tries to rebalance its economy toward consumer spending. However, the growth of disposable income is much slower than that of household debt, and Chinese households are increasingly reluctant to spend on big-ticket items due to growing concerns about job security and the economic outlook. The government has announced lower personal tax rates, but the effect is limited in the short term.

Currently, household leverage in China is generally manageable. China has a very high savings rate, and the household debt-to-GDP ratio is still fairly modest compared with other economies in the region. Outstanding residential mortgages accounted for 54% of total household debt in 2018, up from 50% in 2015, and first-time home buyers make a down payment of 30% or more.

It is easy for consumers to borrow from online peer-to-peer lending platforms, and some short-term consumer loans have been used to invest in the stock market and properties. The government’s crackdown on online financial irregularities have led to reduced availability of these loans.

Closer monitoring required

In Asia Pacific, high or rising household leverage adds pressure to the future economic growth and financial stability. In Australia, although household debt growth moderates, the corrections in the housing market has led to reduced household net worth and slower economic growth. Meanwhile, elevated household debt also remains a major problem in countries like China, South Korea, Malaysia and Thailand. Household debt grows faster than disposable income in these countries, which is depressing household spending. The governments should continue to closely monitor the risks posed by high household leverage, and financial institutions need to control their loan product quality.