Within Africa, the South African banking sector has long been viewed as benchmark setters for industry best practice within the continent. However, other emerging markets may soon become real competitors as new banking hubs develop. Although the transaction banking business continues to be the backbone of the banking industry in Africa, retail banking is now edging into the forefront of growth, with huge potential in the region’s large unbanked population.

Sub-Sahara Africa, which can be subdivided into three distinct regions—West Africa, East Africa and South Africa—has one country in each of these regions that is showing strong economic and banking development. South Africa still serves as the benchmark for East and West Africa, but the latter have developed their own banking hubs with Nigeria and Kenya playing significant roles.

It’s all about the data

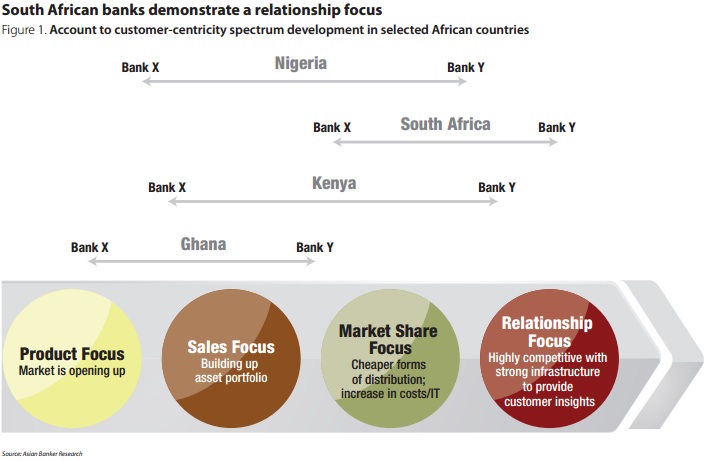

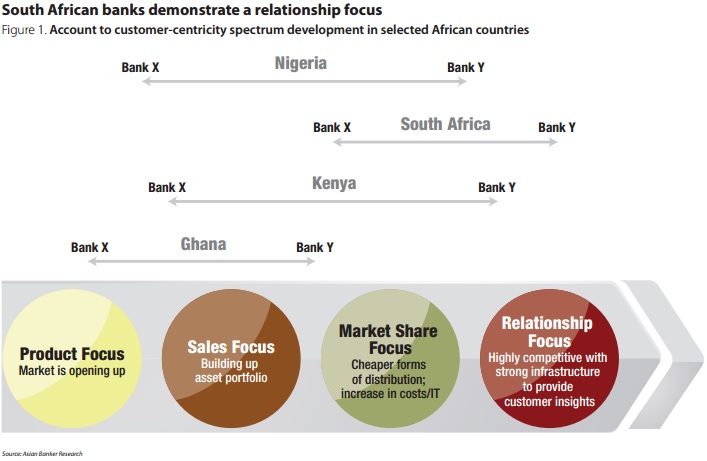

Historically, retail banking markets have moved through four distinctive evolution phases, transiting from a product to a relationship-based focus along an account-to-customer-centricity spectrum. Driven initially through the first two phases—product focus and sales focus—by market opportunity, e.g. the ability to provide banking services to unbanked populations, the subsequent two stages—market share focus and relationship focus—are mainly driven by net margin pressures as competition increases.

Traditional retail banking market developments are being undermined by technological advancements enabling non-bank players to enter the space and take ownership of retail customer data, a key component for relationship-based banking to occur. In fact, given the technological developments, banks in the future may look at becoming asset light businesses where fee generation is more profitable than balance sheet portfolio developments. This will further underline the need for banks to be able to access and analyse customer data to create fee earning, value-added services.

Banks in Africa have been developing along the traditional account-to-customer-centricity spectrum, gradually reaching out to the continent’s very large unbanked population. However technological changes mean that movement towards relationship-based banking is becoming more imperative.

As Fig 1 shows, South Africa is currently the only country in Africa that has institutions that have made the strategic decision to advance into relationship-based banking, realising the importance of deepening the current customer relationship to retain and expand market share. Banks in Kenya and Nigeria are straddling between the sales focus and market share focus stages. Nigeria in West Africa, with one of the largest unbanked populations on the continent, is still predominantly in the sales focused stage, with banks trying to reach more customers through cost effective strategies. Other banks in East Africa are looking at regaining market share from non-bank players able to offer payments services.

Banks in East and West Africa have been struggling to achieve a customer-centric approach. From our research, only six out of 10 banks in West Africa have begun on this quest, and of these only 20% have the capability for staying customer-focused. Banks that achieve a customer-centric approach are able to create technology infrastructures that capture both transaction and relationship data that can be used to produce tailored products and empower front line staff to better serve customers. Data capture can be more easily achieved by incentivising customers to use alternative channels. South African banks leading the way in this regard include Standard Bank, Capitec and First National Bank.

Even though these South African banks demonstrate customer-centricity indicating that there has been significant investment in technology and staff development, a comparison of cost-income ratios across the three African regions (Fig 2) show that these ratios are relatively similar across Sub-Saharan Africa.

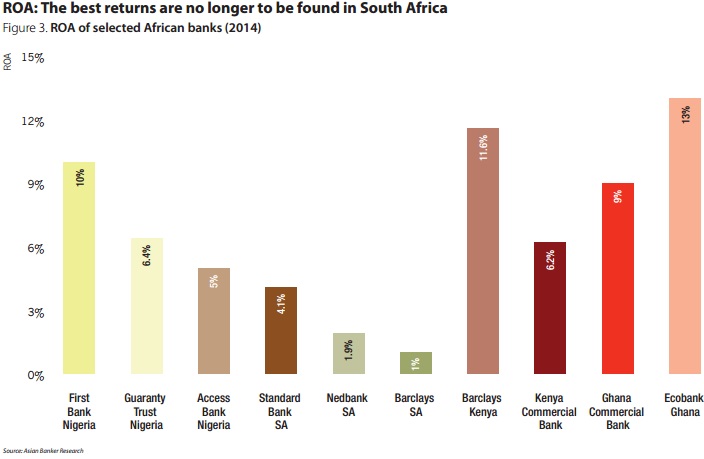

On the other hand return-on-asset (ROA) comparisons are showing significant differences depending on the region (Fig 3).

South Africa has seen stagnant growth with much lower returns for the retail segment while still maintaining above 50% cost-to-income ratios. Many of the banks in Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya maintain similar cost-to-income ratios but have a much higher ROA for the retail segment in 2014 compared to the leading banks in South Africa.

Banks in Nigeria and Ghana may have been unwilling to make technology investments since ROA remains strong in these countries and net interest margins have not come under any undue pressure. For example net interest margins in Kenya have remained strong and stable, helped by high interest rates, but with the potential to grow in the marketplace, banks should be seeking to capitalise on this now, bringing down their cost-income ratio.

Retail revenue opportunity

Many of the African continent’s largest economies still have a high percentage of unbanked residents (Fig 4) but this is changing. As GDP rises, an increasing percentage of the formerly unbanked will seek retail banking services, including payments services.

South Africa still has the highest percentage of retail assets even though Kenya has a slightly lower unbanked population (Fig 5), no doubt partly due to more sophisticated relationship banking on offer from the country’s banks.

The higher asset returns available in East and West Africa have not gone unnoticed by South African banks. South Africa’s stagnant economy is making growth challenging. As a result there has been some market consolidation. Barclays has almost doubled its retail assets following its acquisition of ABSA in 2013, and several of its banks have been relying on returns from their investments in East and West Africa. For example Standard Bank (Stanbic), Barclays and Nedbank have looked to their branches in East and West Africa for increased revenue. Nedbank has benefitted from its shareholding in the Ecobank group, while Stanbic has seen an almost $9 million increase in revenue largely due to its continued focus on the SME segment.

Banks in East and West Africa have stepped up their strategic initiatives in response to competition. In Nigeria, First Bank of Nigeria has aggressively sought to grow its retail asset base since 2010, executing a strategy to be the largest player in the Nigerian marketplace by building on its extensive branch network. It has succeeded—with over a 40% market share of customer deposits, and a 21% share of gross loans, the bank became the biggest retail lender in Nigeria by year-end 2014. As the oldest bank in the country, First Bank was one of the first to service retail customers.

In Ghana, even though Ghana Commercial Bank (GCB) saw a decline in retail assets during the past few years, largely tied to a poor reputation for customer service, the bank has invested heavily in technology, and in 2014 repositioned and rebranded itself as GCB in order to capitalise on opportunities in retail banking.

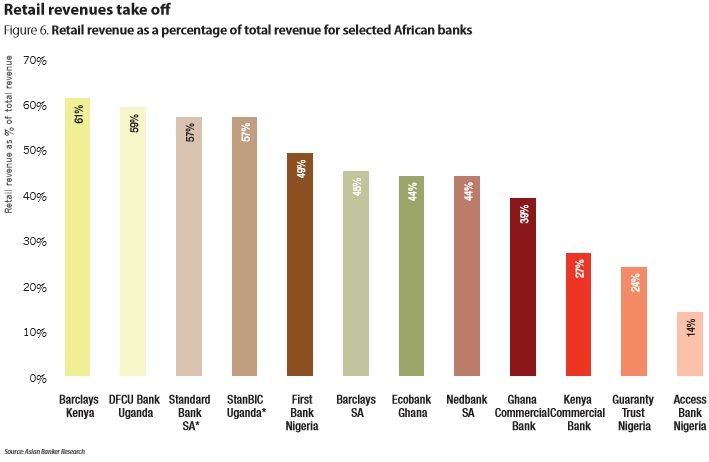

The extent of this recent investment activity in retail banking has resulted in some African banks receiving a higher proportion of their revenue from retail banking than commercial banking, the traditional major revenue source (Fig 6).

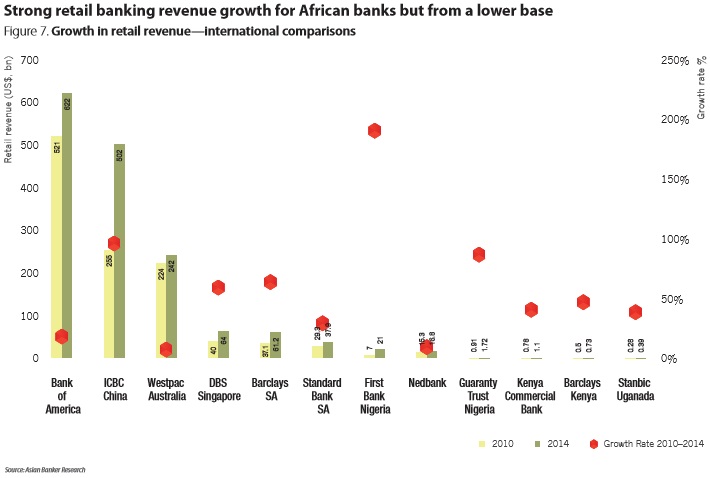

To put the recent opportunities in retail revenue in Africa in perspective, international comparisons are useful (Fig 7). Although retail revenue (fee income and interest income) growth rates have in some cases been stellar among African banks, the actual revenue generated by major banks across the Sub-Sahara African region as a whole is still low compared to major banks in other continents. For example, Barclays SA generates the same level of revenue as DBS Singapore in a country with a tenth of the population of South Africa, a reflection of the differing levels of GDP per capita (South Afirca’s GDP per capita is roughly one-tenth that of Singapore).

Retail banking landscape

With its large unbanked population, the retail opportunity in Africa is compelling. In order to contain costs and remain competitive while expanding their customer base, banks in all three regions are implementing multiple strategies to enable them to expand their reach and physical presence; an expansive branch structure is still a requirement in this part of the world.

A more developed infrastructure is enabling banks in South Africa to avoid some brick-and-mortar developments by introducing virtual tellers available after hours. Major South African banks such as First National Bank, Stanbic, Nedbank and Barclays have implemented strategies to introduce “electronic branch” models. These models use the branch to acquaint customers with new technologies that drive alternative channels, such as showcasing iPad banking in the branch to enable customers to do the same at home.

Agency banking, or reaching customers through secondary service providers, has met with some success in East Africa where an agency network of over 40,000 agents exists. For example Equity Bank has 155 branches in Kenya and also maintains an agency banking network of approximately 21,100 agents. This has resulted in a 38.5% increase in agency transactions as at end Q2 2015, overtaking total branch and ATM transactions and lowering costs for the bank.

In Northern Nigeria there is a general consensus that the use of agency banking and alternate channels should represent the best way to avoid brick-and-mortar outlets but there are challenges to overcome. Current electronic processes within the Nigerian banking system remain complex and West African agents own the customer rather than the bank. This ownership structure makes the cost benefit analysis challenging as the bank cannot determine the cost of serving the customer. In addition, there are problems with capacity and quality of agents, the cost efficiency of agency businesses and security issues related to agency banking. As a result, agency banking has not taken off in Nigeria even as banks look at Kenya’s model to address these issues.

The West Africa banking industry is struggling to find the optimal branch model for cost effective expansion. Mobile banking centres are being explored as a new way to reach the unbanked and provide basic services. However costs remain high and there is an issue of security. Another rising trend in the region is the use of shipping containers as bank centres in remote areas, as they are portable and low cost.

Maintaining profitable growth

For emerging markets, infrastructure plays an important role in banks’ technology decisions, which helps explain the slow adoption of internet banking and the faster uptake of mobile banking in Africa. African banks are looking for technology solutions that enable them to offer the same kind of service across all channels with the greatest emphasis being placed on mobile banking. Banks are playing catch up in payments and collections as telcos have provided payments platforms across Africa. In 2014 East Africa saw a decline in the number of card transactions while transactions using MPESA, a mobile phone-based money transfer service, increased tenfold. New threats to banks could still come from brands like Alibaba and Apple. ApplePay is not the only competition, Facebook has 1.3 billion daily users, and it is only a matter of time before they apply for a banking licence.

In order to overcome these challenges, banks need to provide value to customers. Banks across East and West Africa are only competing to increase their market share and are not looking at their long-term strategy. They are still in the product and market share focused phases along the account-to-customer-centricity spectrum, but they should actively consider ways they can move to a relationship focus. For example, banks should consider changing customer buying behaviour, where some customers shop online, some though physical outlets, and some through mobile, but in each case the payment experience required is different. Customers will always want the highest results for the least effort. Although mobile banking is a driver for long-term gain, it requires a clear vision in order to succeed.

By providing simple, affordable payments options to customers, telcos have begun to compete in areas that were formerly the sole preserve of banks in Kenya and East Africa. Now that the merchant and customer can interact with each other directly they do not need the bank to transfer money. This transformation has been helped by the advent of mobile wallets. Control of the mobile wallet is essential; if banks lose their relationship with the customer, the customer will simply deposit his salary with the bank, and use mobile wallets to make purchases. Prior to mobile wallets, banks made money by charging a premium for money transfers, but the new generation of online payments players is demonetising transactions.

In East Africa, even with the success of services such as MPESA, banks are still able to compete in this new competitive environment but they need to understand what people use mobile money for, such as air time recharge rather than transferring funds as the general population is not yet comfortable sending money on this platform.

By comparison, telecom-led financial services in Nigeria have not had the same level of success due to strong action by regulators. Regulators want financial services to remain bank-led, although there are disruptions from non-bank players such as Paga and Paypal. In order to encourage digital money solutions, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has implemented a cash transaction policy penalising banks and customers for large amounts of cash handling. However, there is still a lack of trust in digital money and physical cash is still preferred and the rate of adoption has been slow.

Mobile banking in North Nigeria presents a unique opportunity for banks; over 40 million adult Nigerians remain unbanked due to the conditions in the country. While almost everyone has a mobile phone in North Nigeria, only a small percentage of those phones are smartphones, making mobile banking penetration extremely low. Even among those who do have smartphones, many are not sufficiently literate to bank using their phones. If banks have support from the central bank, as in the case of the Bank Verification Number initiative that promotes the use of biometric identification rather than traditional paper-based verification methods, it might be possible to get mobile banking to North Nigeria. The CBN can also help to market banking services in local languages and dialects. In this region, telco operators can be partnered with and used to reach these people. However, one of the main barriers to success lies with the banking system; banks have yet to implement technology and methodologies that capture and enable non-smartphone users.

When considering ways to reach the unbanked, South Africa will need to look at East and West Africa to see what engagement models work best. South Africa lags behind its counterparts in this regard and in innovative mobile payment adoption.

The competition from non-banks is happening in customer adoption and acquisition, so banks across Africa must consider both their level of collaboration with telcos and their own value service to the customer. There, the potential for the players who are able to break into the unbanked markets in Africa remains huge.