- VCs poured a record $8.6 billion into Asian fintech in 2016, up almost 50% from year before

- Traditionally, regulators take on the role of cautious custodians but this needs to grow where regulators facilitate an environment that is based on cooperation

- Regulators need to capture the right balance of encouraging innovation and protecting consumers, while keeping an even playing field

While venture funding into technology dwindled last year, the one sector bucking this trend was fintech in Asia. Venture capitalists poured a record $8.6 billion into Asian fintech in 2016, almost 50% up from the year before. Meanwhile, funding for fintech globally had almost halved.

It is no wonder that investors see such promise in the sector. Billed as the democratisation of the financial services, the industry is trying to bank those that have been forgotten, or left behind. The challenge for regulators, and it is a big one, is to capture the right balance of encouraging innovation, while protecting consumers.

"The role of regulators needs to change," says Tobias Fischer, director of corporate development at Capital Match, a peer-to-peer (P2P) marketplace lending platform, and regional fintech advisor to the Asian Development Bank.

"Traditionally, regulators take on the role of cautious custodians but this needs to grow where regulators facilitate an environment that is based on cooperation."

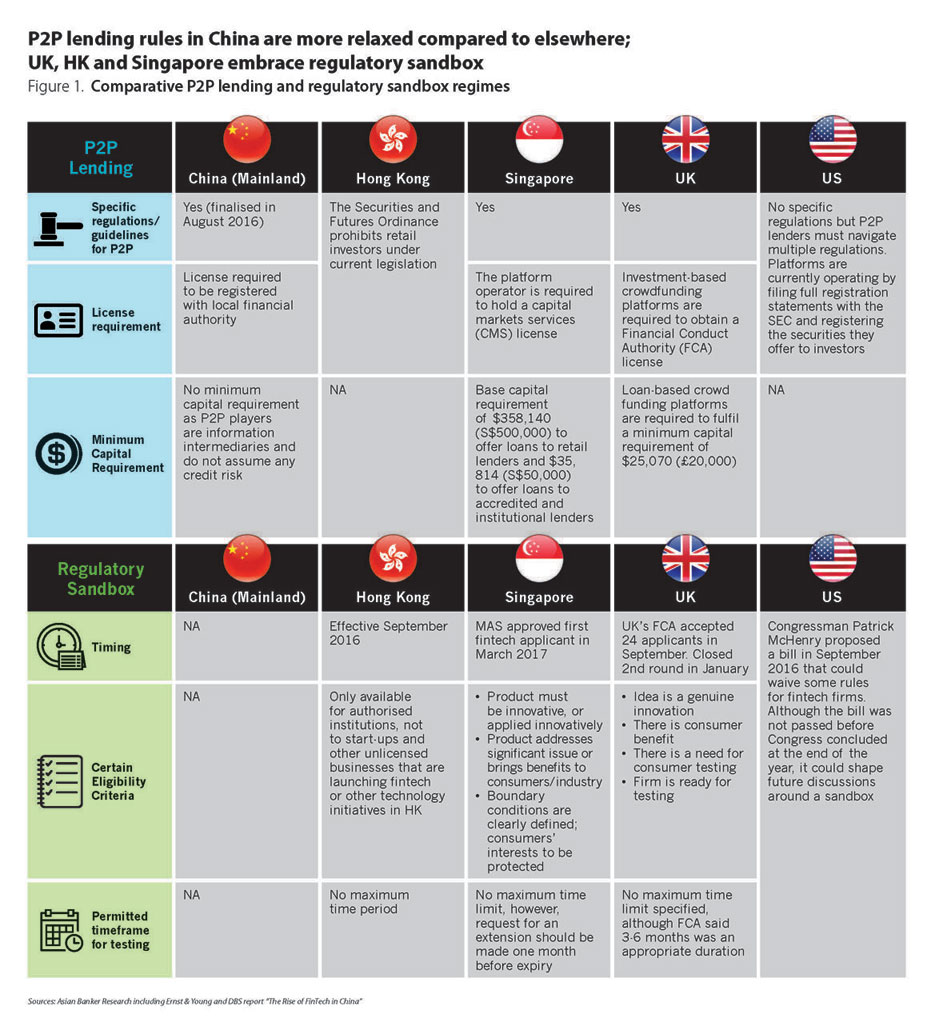

One example of this is the regulatory sandbox. After the United Kingdom launched the first sandbox in November 2015, many countries including Australia, Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong and Brunei, have all launched similar schemes.

The sandbox basically creates a controlled environment for businesses to test products with less risk of being punished by the regulator. In early March, the Monetary Authority of Singapore picked insurer PolicyPal to be the first entrant in its programme.

Comparing all these regulatory initiatives, China has taken a much more laissez faire attitude when it comes to industry rules. Perhaps, as a consequence, fintech have become so advanced that payment for a house or a car can be “beeped” through a mobile phone.

Yet there are also risks to such freedom. One shocking case is Ezubao, which lured investors with offers of double-digit returns and became China’s largest online financing platform in just 18 months. The company attracted $7.6 billion from 900,000 users before being identified as a Ponzi scheme with more than 95% of borrowers being made-up.

"The biggest issue is that the very nature of fintech means it is evolving and changing," said Antony Eldridge, Singapore financial services leader and Asia Pacific banking and capital markets leader at PwC. "And therefore regulators need to be keeping their eyes on it. The other challenge, is not only how quickly innovation changes but how quickly some of these services can grow to be systemic."

Since Ezubao, China has implemented a more pronounced regulatory approach. Rules have been imposed on credit limits and the prohibition of pooling and lending of funds by P2P platforms. These companies also require a principal guarantee and debt securitisation to mitigate lenders’ credit risks.

Finally, a 400-strong task force under the National Internet Finance Association was created to police the industry. Yet, China’s regulations still remain less onerous, where P2P players do not need a license or have minimum capital requirements, unlike Singapore or the UK.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), the island’s watchdog, has opted to regulate debt and equity based alternative finance platforms within existing regulatory frameworks akin to Hong Kong, while others take a more bespoke stance, such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand.

"Both approaches have their pros and cons," says Capital Match’s Fischer. "Existing regulations have a more profound framework that has been proven for many years. On the other hand, bespoke regulations can be more flexible and relevant to the market."

Indonesia released new regulations on P2P lending in January. Some of the key points being that lenders need to apply for a licence, loans have to be capped at IDR2 billion ($149,410) and any loans startup needs to have access to at least IDR2.5 billion ($186,000) of capital.

Not only do regulators need to straddle the difficult balance between innovation and customer protection, but they also need to be wary of creating an uneven playing field.

Since the global financial crisis and Lehman Brother’s collapse, banks have to follow onerous rules to ensure they are well-capitalised. Of course, most fintech companies do not carry such systemic risks, as yet, and should not have to bear the same obligations. But at the same time, fintech companies should not be allowed to pay less significance to compliance.

"Unlike other sectors, fintech need to be on top of regulations from day one," said Adrian Fisher, technology, media and telecommunications counsel at Linklaters.

"They can’t wait until they grow to a certain size for example to pay lawyers to clean up corporate governance. For fintech, if they don’t have a particular license but they need one, it kills their business model."

The problem with this, of course, is that it costs quite a bit of money, especially for a business in its infancy. Singapore’s MAS has recognised this stumbling block, and facilitates legal consultations for start-ups.

Despite the regulatory advances, however, founders of fintech start-ups still bemoan the current rules as being too onerous or too slow to react. Meanwhile detractors of fintech point to cases like Ezubao as a cautionary tale as to why the industry should be more carefully scrutinised.

The truth is that there are definitely lessons to be learnt from Ezubao and other cases but in a cash society similar illicit activities also flourish. Look no further than Bernie Madoff’s eye watering $20 billion Ponzi scheme. In short, there will always be bad apples in the real and digital world.

Regulators around the world definitely have a challenging job ahead of them. With innovation evolving at breakneck speed, there needs to be a balance between how fast regulators can respond to how quickly the market is moving. All this while keeping the rules fair for all participants.

The Financial Stability Board, which pools regulators from around the world, is assessing how suitable existing rules are for industry. And they are expected to report their findings to G20 leaders in July. That’s definitely a step in the right direction because what is needed in this boundless digital world is for increased dialogue between regulators on a global scale.