- The pandemic has intensified the reshoring and near-shoring of global supply chains

- Stakeholders prioritise stability and security of supply chains over advantages from cost optimisation

- Shifts in global supply chains accelerate demand for dynamic financing programmes

The trend towards diversification of supply chains predates both the US-China decoupling on trade, technology and investment and the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the pandemic has exposed the fragility of far-flung supply chains and accelerated the process of reshoring which means supply chains are moving closer to the centres of consumption or migrating to new markets. This, coupled with the severe squeeze on liquidity during the crisis, has raised the demand for new forms of supply chain financing (SCF) or higher utilisation of existing programmes. Demand for reverse factoring or payables finance has grown significantly as corporates recognise the importance of providing sources of funding and enhanced flexibility to suppliers. These are particularly valuable for small and medium size enterprises (SMEs) that can access more affordable funding based on the creditworthiness of buyers (corporates).

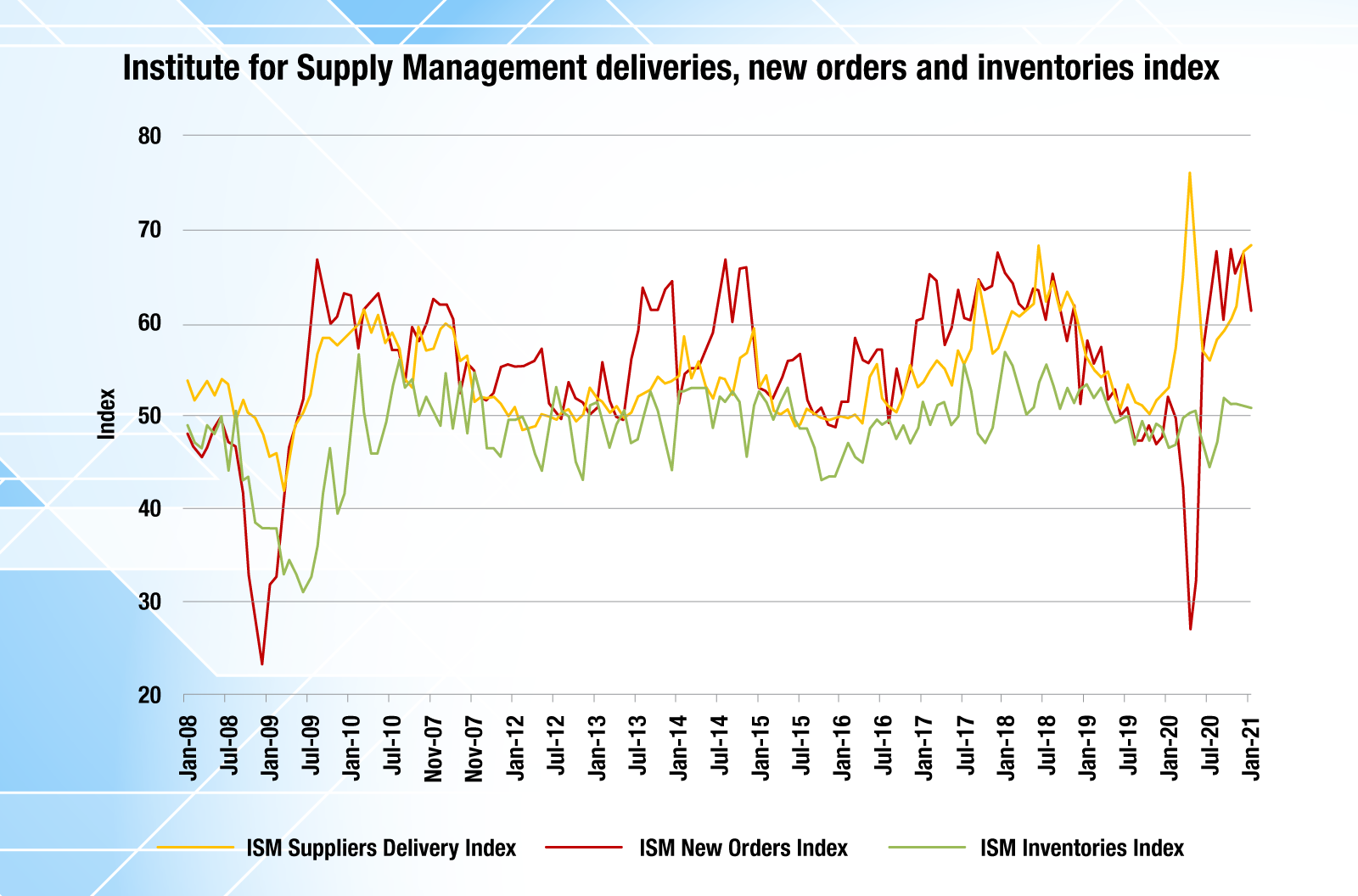

To maximise returns, global supply chains are over-optimised and built on principles of lower labour cost and overhead arbitrage. This disrupted complex and long-established supply chains during the pandemic. Paula Da Silva, head of transaction services at SEB, a Swedish corporate bank, observed production bottlenecks in Asia distorted global supply chains across the world. “If you are dependent on supplies in your production from another part of the world such as Asia and China, that has slowed down.” After major mobility restrictions have been relaxed, suppliers continue to face bottlenecks in maintaining delivery rates due to factory labour safety issues and transportation challenges, according to the Institute for Supply Management latest report on business (Figure 1).

Suppliers’ deliveries and inventories are still experiencing labour and component constraints

Figure 1: Manufacturing on the mend but supply bottlenecks remain

Source: Asian Banker Research, Institute for Supply Management

Notes: A reading above 50 indicates expansion; below 50 shows contraction

Global supply chains on the move

The relocation of supply chains to national borders has been underway since the US-China tension. The supply disruption brought about by the pandemic accelerated the need for firms to source inputs and manufacture locally. The Bank of America (BofA) Global Fund Manager Survey showed that 67% of participants cited “localisation or reshoring of supply chains as the most dominant structural shift in the post-pandemic world”.

“We continue to see the trend towards geographical diversification of supply chains,” said Peter Jameson, head of Asia Pacific trade and supply chain finance, global transaction services at BofA. He said the trend on reshoring is somewhat an imperfect but natural hedge against inefficient movement of goods. The goods produced closer to centres of consumption make up for lost efficiencies that arise as part of labour cost arbitrage and lower overheads. “In 2019-2020, the trend with supply chains moving closer to the end consumer increased.”

The trend of moving back to home markets intensified, became more complex and gave way to leaner and agile supply chains. “While it may take years to move long-established production and logistical infrastructure bases, the pandemic underscored the need to do more near-shoring as corporates break up large purchase order (PO) into smaller and nimbler supply chains,” said Michael Sugirin, global head of open account trade and trade implementation at Standard Chartered.

Corporates with global and regional manufacturing networks are moving operations out of overly concentrated geographies to new markets. There is growing reshoring in China and parts of Southeast and South Asia. “Few clients are seeking to move out of existing markets and considering placing additional capacity in new markets. Southeast Asia, particularly Vietnam, has been a beneficiary of this,” added Jameson.

“There was significant discussion last year because of the US-China trade tensions that raised concern around moving factories away from the North into potentially Southeast Asia or India,” pointed Sugirin.

Early stages of crisis called for conserving liquidity

With the drag on consumer spending and production that impacted business flows and working capital cycles, many corporates’ priority was to conserve liquidity position. They preserved cash flows and identified additional sources of credit facilities to boost cash buffers.

Affected companies required longer credit terms from suppliers to conserve cash flow while others cut costs to accumulate more liquidity including tapping into capital market and buffer during the period.

Sugirin noted, “With liquidity squeezing up, corporates and their treasuries have shifted focus to conserve cash by deploying more resources into pre-shipment and dynamic discounting SCF programmes to give suppliers access to liquidity”.

Da Silva added that disruption to demand precipitated the need to support businesses with funding and incentives as quickly as possible to keep the liquidity going. “SEB, with a couple of investors, put forward a fund to support small businesses and their owners to keep companies alive during the pandemic”.

The pandemic has seen a surge in demand for SCF programmes launched by a corporate buyer with a bank or alternative provider to allow suppliers to get paid early for an invoice usually at a discount.

Uptick in utilisation of supply chain finance programmes

The chain of events led to a cash crunch and the drying up of capital and liquidity particularly for SMEs in the supply chain. Several banks reported a notable increase in the utilisation of the SCF programmes. “Given the pressure on market liquidity, companies recognised the importance of providing sources of funding and enhanced flexibility to suppliers and SCF programmes are a great means of achieving this,” pointed Jameson.

For corporate buyers, SCF programmes ensure continuous access to sufficient cash and liquidity to fund purchases and production. However, small suppliers’ access to liquidity in the market became limited.

“When cash and capital are tight, financial institutions (FIs) will dedicate resources to larger corporate buyers including those with SCF programmes over supplier-led programmes,” noted Steven Beck, head of Asian Development Bank’s trade and supply chain finance programme.

“Customers are interested in using working capital rather than having to borrow money from banks,” explained Da Silva. “We have seen unique structures with shorter turnaround time being implemented especially in the retailer's sector that has a huge impact on customers.”

“Corporates had injected funding as part of the dynamic discounting programmes into supply chains to keep suppliers and give them access to liquidity,” said Sugirin.

Corporates bring in more suppliers and support their liquidity needs through dynamic discounting programmes. Corporates leverage the strength of balance sheets to provide liquidity. This method, also known as payables finance or reverse factoring, provides SMEs access to more affordable funding based on buyer's creditworthiness.

Sugirin also emphasised that a lot of corporates are now looking at the next-tier of financing that reaches the smaller cohort that sits at the end of the value chain.

Just-in-time or just-in-case or both

The US-China trade-tech friction put the spotlight on the nature of global supply chains. The inventory management strategies around these are essentially built on decades of cost, speed and working capital optimisation. The pandemic pushed corporates to point not just to the apparent lack of diversification in just-in-time (JIT) supply chains but also the speed with which the crisis affected the supply chains.

Beck said, “The pandemic made society realise that supply chains could be fragile and that poses a risk to delivering vital goods to people when and where needed”.

JIT has become the standard for supply chains built solely on the premise of lowest cost principles. JIT creates a short-term competitive advantage under normal business conditions but it failed the contingency test as inventories were run down. Revenues and ability to meet consumer demand were severely impacted due to breakages in global supply chains and exacerbated further by liquidity constraints. Vikram Sahu, head of Asia Pacific Research at BofA Securities highlighted, “The pandemic underscored the pitfalls of overly optimised, JIT supply chains that are unlikely to be forgotten soon”.

On the flip side, a company with a just-in-case (JIC) supply chain strategy incurs high inventory holding costs in exchange for a reduction in units or amount of sales lost. It remains competitive by being able to ship products immediately as it responds better to new and immediate demand.

The pandemic underscored the need for stakeholders to prioritise security and stability of supply chains over costs. The balance to maintain a sustainable production line can be achieved through a hybrid between JIT and JIC. This means achieving lean processes with sufficient inbuilt flexibility to reconfigure production and procurement. “The set-up depends on the company and industry and a hybrid global supply chain will be appropriate,” said Beck.

Sahu elaborated, “There will be a gradual transition to a JIC inventory system wherein companies will be more accommodating towards leaner processes. They will be open to adding contingent sources of domestic supply for critical items such as strategic sectors including national security, healthcare and pharmaceuticals”.

Acceleration of digitalisation in supply chain financing

Institutions are reinforcing technological capabilities into SCF as they grapple with non-standards of PO and invoice formats. “How can banks help customers transform with standardisation and connectivity to eliminate manual intervention in the future,” asked Da Silva, as she stressed the need for interoperability.

Corporates lack insight whether their suppliers have enough cash to support sourcing needs. The lack of information impedes a richer experience for participants and FIs’ ability to mitigate risks in SCF better.

With near-overnight digital adoption, corporates and their suppliers have been more willing to come to the bank or third party platform channels to digitise from end-to-end. More corporates are looking to digitise their supply chains through investments in procure-to-pay or cloud platforms. Hence, there is a significant uptake of embedding financing solutions into third-party platforms as a way to reach a wider range of suppliers.