- The remittance business remains a large source of bank revenue although the amount being sent to developing countries has contracted

- Partnerships between fintech and banks will flourish to overcome their respective limitations

- Banks have been exploring alternatives that can also provide faster transfer time as the mobile-first approach to remittances become an area of new competition for banks

In the global cross-border money transfer business, traditional global money transfer operators (MTOs) and banks have a lot to fear. A new breed of digital-only players such as Xoom, WorldRemit, Transfer Wise and InstaReM are enabling direct global money transfers sent from and received through mobile wallets held on personal devices. It is a nascent but fast-growing business model aiming to tap into a $600 billion global market this year, with a combination of competitive pricing, responsive and user-friendly web design, greater fee transparency, and better customer service.

In fact, some of the MTOs aim for a much more aggressive route. While current services cover the need of paying bills, airtime top-ups and money transfer via bank or cash pick up, Xoom/PayPal – which has 17 million active clients – wants to cover education, consumer credit, health, and taxes through PayPal Wallet. “As Asian markets grow, we see the need for remittance services growing as well. Many Asian economies are growing and are opening up like China, which has been closed in the past. Furthermore, customers who have been dealing with banks are starting to work with nonbank entities given the cost and speed of transfer. This is a big leap from a trust standpoint,” said Blaine Fabi, president, APAC at InstaReM.

Around 400 million of the two billion unbanked people in the world have some forms of mobile money account. The global remittance revenue generated from digital channels is estimated to be less than 6% of the total but is progressively growing. However, a predominant endto-end digital scenario is still some time off.

Globally, migrant workers send more than 90% of their remittances through off-line channels, which is a key profit driver for the incumbents like Western Union, banks, and pawnshops. However, such transactions usually involve a string of agents and bank networks that increase built-in costs and inefficiencies. Also, emerging countries and regions adopt digital cross-border money transfers with varying speeds. For instance, mobile phones for funds transfer in Tanzania, Kenya, and South Africa outdo those of the most developed countries while similar initiatives riding on the basic Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD) technology such as in India failed to take off.

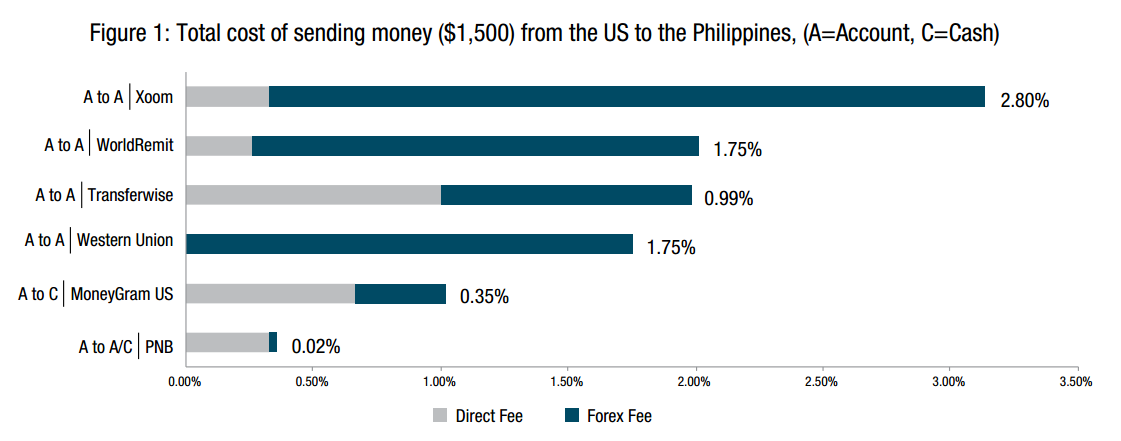

Although digital MTOs lack scope and scale, they successfully compete on fees, particularly forex fees. Digital MTOs offer forex rates that are closer to interbank rates on most transactions, regardless of size, which has increased pressure on incumbents like Western Union and MoneyGram (Figure 1).

New fintech money transfer services compete with incumbents on fees

Note: Total fee structure based on MTOs/Banks’ forex rates and interbank rates from 13 October 2016. PNB is Philippine National Bank

Source: Asian Banker Research.

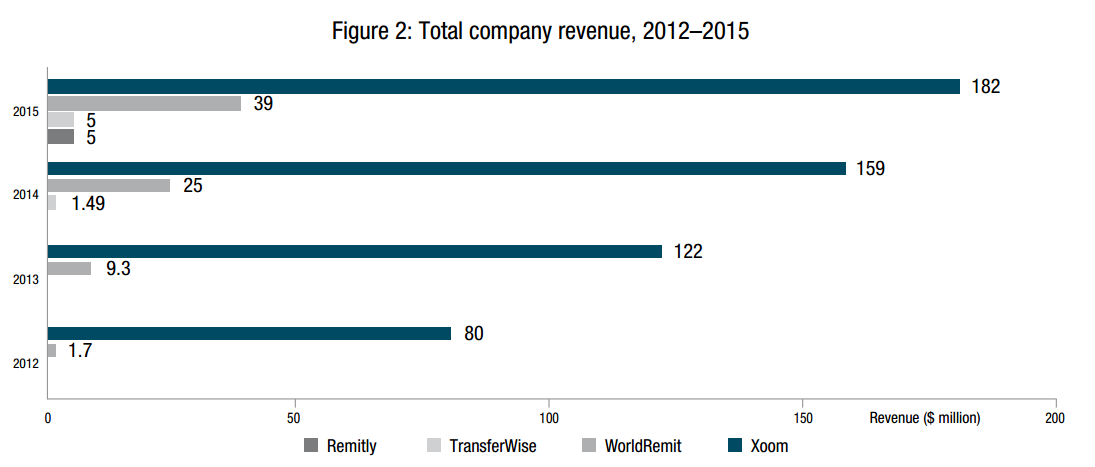

The operating income of Western Union and MoneyGram, the two largest MTOs, have been either stagnant or in decline since 2010. On the other hand, most fintech MTOs have been gaining traction on top line revenue but have been struggling to break even due to expansion costs (Figure 2). For instance, Transferwise’s expenses hampered the platform in making a profit. Its marketing spend jumped from $11.78 million (£9.37 million) in 2015 to $15.46 million (£12.3 million) in 2016. The cost of sales also skyrocketed from $5.66 million (£4.5 million) in 2015 to $15.59 million (£12.4 million) in 2016 due to expansion. Meanwhile, administrative expenses also doubled to $41.10 million (£32.7 million) from $20.51 million (£16.32 million).

Xoom generates the largest revenue among fintech MTOs

Source: Asian Banker Research.

Challenges for digital money transfer operators

Price advantage itself might not be enough for digital MTOs to compete sustainably against the incumbents. Globally, regulators have tightened know-your-customer (KYC) rules and licensing requirements for international money transfers.

“Many countries are increasing their compliance requirements. In the current environment of increasing security, governments are making sure that they know who is sending money in and out of their countries. This makes it more difficult for new entrants in the remittance sector to set up banking relationships and obtain remittance licenses. For example, we received our Australian remittance license 40 days after submitting our application. The standard processing time at that point was close to three to six months. From our understanding, it is now around 12 months for new applications. Governments are tightening the compliance requirements. For anyone trying to start a remittance business in Asia, it will be difficult,” Fabi said.

Also, most digital-only MTOs continue to have a small pool of origination markets where licensing is key. But their operations in destination markets are also vulnerable as they often operate in partnerships with local licensed correspondents through fund transfer to local bank accounts.

Although this is a more efficient service than the SWIFT international payments infrastructure, smaller local parties are at risk of compliance violations or arbitrary regulatory changes. For example, TransferWise ran into trouble with compliance issues when it worked with a smaller third party operator to enter the US market between 2014 and 2015. On the other hand, after the Central Bank of Nigeria forced all MTOs in the country – except Western Union, MoneyGram, and Ria – to cease operations, WorldRemit lost access to a $20 billion inward remittances market, which has generated close to 500,000 transactions a year for the company. Western Union had a dominant position of more than 70% when the central bank attempted to break its exclusive agreements with Nigerian banks.

Asian Banker Research expects increasing partnerships between fintech players and telecommunication providers. There is a natural growth opportunity for telcos in the financial services especially in emerging markets, which have seen rapid mobile and smartphone adoption. However, in a fintech-telco alliance, telcos might not have the power to decide on the fee as part of the agreement. Moreover, they can also deprive commercial banks from accessing data on transaction patterns. This event may happen since telcos and fintech MTOs can position themselves between the banks and their customers.

Digital remittance players

Xoom

Xoom, founded in 2001, was acquired by PayPal in 2015. The company has built a very successful US-centred brand, where consumers are previously hesitant to trust a new player that does not offer greater material value than existing services.

Before it was acquired by Paypal, Xoom has an active customer pool of 1.3 million who send more than $7 billion to 37 countries. However, since it operates only from one sent market and has failed to enter Europe, Xoom has reached its growth ceiling. It remains to be seen how PayPal can accelerate the building up of its sent markets. “Before it was acquired, Xoom has already started entering emerging markets like Mexico, India, Philippines, China, and Brazil. However, this has been in terms of receiving money electronically. What Xoom has capitalised on is the real-time payment infrastructure which is being established around the world, and this is how it entered India for instance. What it has yet to do is establishing ‘send operations’ from other markets. For me, the success of this venture hinges on the question of whether with Xoom, PayPal has better success in the last mile in India, China, and other key emerging markets. To achieve the ubiquity of Western Union and MoneyGram, PayPal will need to address the needed remittance corridors in more than 200 countries and territories, and do this rapidly,” said digital money, payments and remittances expert Charmaine Oakwood.

WorldRemit

WorldRemit offers remittance services in 50 “sender” markets and more than 125 “receiver” markets. Receivers have options to receive money through bank transfers, cash pick-ups, mobile money wallets, or airtime top-ups. The company, which has a global workforce of 200, grew its fee-based revenue from $1.7 million in 2012 to $39 million in 2015 by targeting migrant workers. It has also reiterated to The Asian Banker in a recent interview that it is on track to break even in 2016. The mobile money option is at the core of its operations, and the company intends to make it the primary transfer business over the next decade. WorldRemit has more than 260 mobile wallet providers and messaging apps globally.

Much of the future growth will come from Asia Pacific and Australia, given their high number of sending and receiving corridors. The company has partnered with Safaricom’s M-PESA, international banks, and mobile operators to facilitate money transfers to clients, especially in emerging markets like India, Philippines, Vietnam, and Bangladesh. It has also partnered with UAE Exchange to integrate its Payout application programme interface (API) that can process a large number of requests. In 2016, WorldRemit set up a shop in Australia, the second largest sender market after the United Kingdom with 80,000 transactions per month. In addition, the company has teamed up with African carrier MTN, which has 22.5 million users in 16 countries in the region.

InstaReM

InstaReM comprised of an experienced team in information technology, banking, and money remittance. The core team has built and run several finance companies in countries including Australia, Singapore, USA, India, and Canada.

The company has teamed up with around 15 banks in Asia Pacific, and has planned to expand its partnership with banks and payment processors. Since it was launched in March 2015 in Australia, InstaReM has expanded its services to other locations like Hong Kong and Australia.

“We have just launched Hong Kong as a sending location. In Australia, we are sending 8,000-10,000 transactions per month with a volume of $12-15 million (A$ 16-20 million),” Fabi said.

As of August 2015, instaReM has received remittance licenses in Australia, Canada, and Hong Kong. On the fund receiver side, the list includes India, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Philippines, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Hong Kong. It will soon add China, North America, and Europe to the receiver list.

“We are a money remittance company, but we are planning to offer products outside of remittance, which will complement our core product. We are working on new services that are designed to increase financial inclusion of millions of under and non-banked people in Asia. We are also working on banking solutions for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that will give them the same level of banking service that large corporations enjoy. Regarding the cost, we offer close to inter-bank rates on all transactions, big or small,” Fabi explained.

Digitisation of remittances services by commercial banks

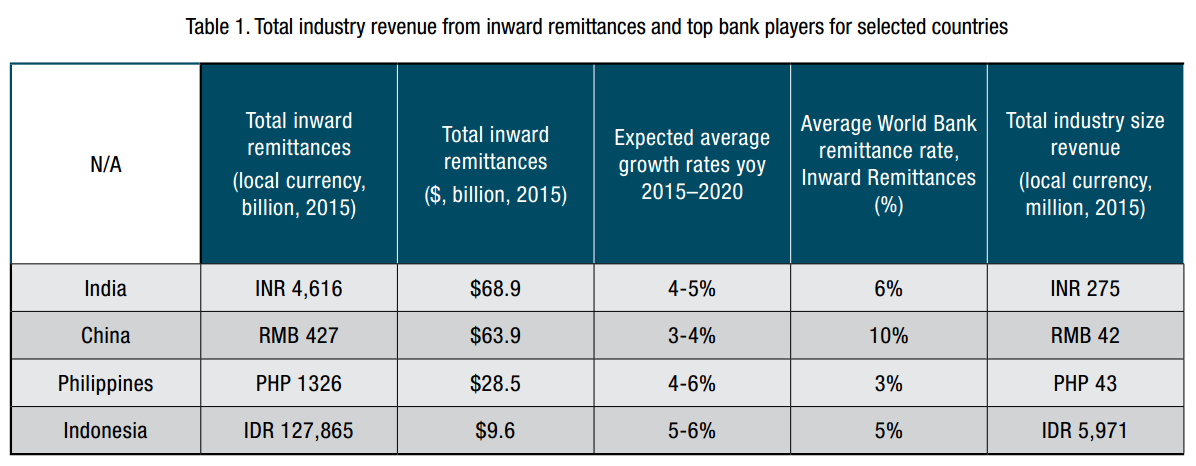

Remittance is still a large source of revenue for banks despite the contracting amount of remittances to developing countries in 2015, which only registered at $431.6 billion – a muted increase of 0.4% from $430 billion in 2014. Decreasing flows from Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries due to an oil price slump have resulted to this minimal rise. On the other hand, India sustained its position as the largest remittance recipient with about $69 billion in remittances despite a slight decrease from $70 billion in 2014. Other large recipients in 2015 were China and the Philippines with $64 billion and $28 billion, respectively (Table 1).

India continues to receive the largest remittance volume globally

Note: BCA’s remittance volume includes all inward and outward transactions from all customer types, including corporations and individual workers

Source: Asian Banker Research.

For banks, the mobile-first approach to remittances is an area of new competition. However, since SWIFT-based traditional transfer services have become too expensive, banks have been exploring alternatives that can also provide faster transfer time. Regular transfer services using SWIFT takes a time to reach the beneficiary unlike the competitive services offered by exchange houses and money transfer operators, which deliver within one to two days. Banks are ready to partner with fintechs for money transfer services on a case-by-case basis especially if it presents additional value and if they feel comfortable with the fintechs’ compliance regime.

For example, Emirates NBD introduced its flagship DirectRemit service in 2014 that allowed customers, mainly expatriates, to transfer money to their home countries within 60 seconds, free of charge. “Expatriates are a significant portion of our customer base who need to send money home regularly, making remittances is an important service,” said Suvo Sarkar, senior executive vice president and group head, retail banking and wealth management at Emirates NBD. The move resulted in a ten times growth in terms of remittances and six times growth in value between 2014 and 2015.

The service, which was initially launched in India and Philippines, was extended to Pakistan and Sri Lanka in 2015. The bank also offered DirectRemit in Egypt this year as it expects to open more corridors. At the same time, the bank launched DirectRemit 2 Mobile, which allows customers to remit funds through the bank’s mobile banking services. Earlier this year, the service was equipped with a cash delivery option for the Indian corridor.

“The markets where we have launched the service are leading remittance corridors from the UAE. Our service will help customers send money home instantly, free of charge, and at market benchmarked rates. DirectRemit is also available on mobile, making it easier for customers to send money at their convenience,” added Sarkar.

Emirates NBD has established strategic partnerships with some leading banks in home countries to reduce the cost and time of the money transfer service. These banks include HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank, SBI and Axis Bank in India; Banco De Oro in the Philippines; Faysal Bank in Pakistan; Hatton National Bank in Sri Lanka; and Emirates NBD’s subsidiary in Egypt.

A secured integration of third party systems with partner banks has been achieved using API-based interfaces, which enabled instant credits at negligible cost. As a result, mobile transactions for international and local transfers have grown. Also, growth in local mobile transfers outperformed international transfers by a factor of 5 in 2015.

Conclusion

Most fintech remittance providers understand the value of partnering with banks. Regulatory-wise, they cannot hold deposits and are reliant on banks or telcos for “cash out” or access to deposit accounts. This is partly due to weak national e-payment infrastructure and heavy cashbased payment behaviour in many emerging markets in Asia. However, with new national payment infrastructure upgrades in several countries like India and the Philippines – and growing merchant network adoption of micro- and e-payments – mobile money, and wallets will be more prevalent in the future. Such transition will cut customers’ overreliance on banks. We also expect more fintechs to partner with telcos whose reload agent networks outnumber the branch networks of the largest banks such as in Africa and the Philippines.